|

Within a few hours of the Alcolu murders on March 24, 1944, the

families of the missing girls were already frantic. It was very

unusual for the girls not to return home on time. Since they were

always playing in the woods and were familiar with the local

countryside, it was unlikely they were lost. The local lumber mill,

Alderman Lumber Company, organized a search party that consisted of

their employees and almost everyone who lived in Alcolu. The

operation was under the direction of B.G. Alderman, owner of the

lumber company, and included both blacks and whites. Although

they searched throughout the night, they could not find the missing

girls. Then, at about 7:30 in the morning of the next day, some of

the men found small footprints in the soft ground. They followed the

trail and soon discovered a pair of scissors. It was already known

that Betty June had taken these same scissors from her home to cut

flowers. Within minutes, the search party came upon a water

filled ditch, surrounded by thick, thorn covered bushes. The bushes

showed signs of being crushed. In the ditch, the faint outline of a

child’s bicycle could be seen under the water. “There’s the

girls!” one of the searchers screamed. Scott Lowden, a

member of the search party, jumped into the muddy hole and the

bodies of the missing girls were finally found. Betty June had

severe head wounds in the back of the skull. Mary Emma had five

separate skull fractures. The cause of death in both cases was later

determined to be severe trauma to the head. The girls had been

viciously beaten with a heavy, blunt object.

After a few hours of investigation, the local sheriff deputies

located and arrested George Stinney Jr. who neighbors had seen in

the area where the girls were found. He was brought to the local

sheriff’s office where police interrogated him. Since 1944 was

long before the Warren Court era, there were no Miranda Warnings,

even to a juvenile. The interrogation continued without a parent

being present or attorney representation. Clarendon County Sheriff's

Deputy H. S. Newman and a representative did the questioning from

the Governor’s Office, Officer S.J. Pratt ( The State, March 26,

1944). In less than one hour, Stinney confessed to the crime.

Deputy H.S. Newman later described the event for the court: “I

was notified that the bodies had been found. I went down to where

the bodies were at. I found Mary Emma she was rite at the edge of

the ditch with four or five wounds on her head, on the other side of

the ditch the Binnicker girl, were laying there with 4 or 5 wounds

in her head, the bicycle which the little girls had were side of the

little Binnicker girl. By information I received I arrested a boy by

the name of George Stinney, he then made a confession and told me

where a piece of iron about 15 inches long were, he said he put it

in a ditch about 6 feet from the bicycle which was lying in the

ditch” (from Deputy Newman’s written statement, March 26, 1944).

Later that same day, Stinney voluntarily led police to the crime

scene, a short distance outside of the town, where the murder

weapon, a large railroad spike, at least 14 inches long, was

recovered

Immediately, there was grief and outrage in Alcolu. Never before

had such a horrendous crime occurred in Clarendon County. Mill

workers were especially angered since both girls had relatives who

worked at the mill. Passions became further inflamed when details of

the crime, supplied by Stinney, became public. The young defendant

told police that he killed Mary Ellen because he wanted to have sex

with Betty June, the older girl. Angry townspeople and mill workers

gathered together in Alcolu and they quickly formed into a mob. On

the night of March 26, 1944, a mob of angry whites headed for the

Clarendon County jail to administer mob justice. Although, lynching[1]

was actually rare in the 1940s, the bitter memories of Southern

vigilantism from the 1920s and 30s are a sad part of America’s

history. But sheriff’s deputies wisely escorted Stinney out

of the county jail to the City of Columbia in adjoining Sumter

County where he was held in a more secure facility for his own

safety.

|

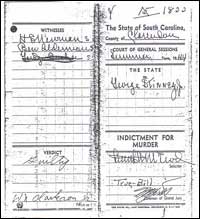

Dated April 4, 1944. The actual

indictment of Stinney, charging him with the murder of Betty

Jean Binnicker

(POLICE) |

[1]

The term “lynching” is derived from the name of Colonel Charles

Lynch of Virginia. During the 1780s, Lynch took it upon himself to

hold illegal trials of lawbreakers after which he would inflict

whippings upon the convicts (Friedman, p. 189)

|