"Erik's coming home," his mother told me. "I'm grinning from here to here," she said later. Ever since his arrest, Sheri Audé had been waging a non-stop battle to bring Erik home. She had talked with attorneys, experts in the field of international law, she had petitioned the President and Vice President of the United States. She had targeted key legislators, and had pressed her own congressman to never give up the fight to free Erik. She even pressed the now convicted drug dealer Rai - his real name was Rasmik Minasian - to admit in federal court that he hired Erik as a drug mule but never told him what was in the suitcases he had been carrying.

It was a long, slow battle and it cost her almost everything. She had to sell the house in Lancaster, the place on the edge of town where she had built what amounted to a shrine to her son.

But her efforts finally paid off.

In early December, after appeals from both Rep. Howard McKeon, her congressman, and Gov. Bill Richardson, who had served under Bill Clinton, a Pakistani judge overturned Erik's seven years sentence and ordered him released on time served.

Four days before Christmas, he was at last released. In fact, his mother said, he was supposed to have been home for Christmas, and she had enlisted his supporters, the people who stuck by him, and by Sheri every step of the way, to help locate a Christmas tree.

Then of course, the flight delays hit America's airports, and Erik Audé, on the last leg home, had to wait an extra day.

It was frustrating, of course, but Erik swallowed his disappointment.

He had been through so much. Beatings by other prisoners, watching them go to their deaths on the gallows. Parasites had eaten away at him, at one point he had lost 60 pounds. But he's a survivor, a young man, who even managed to keep some of his muscle tone while confined in a place that would reduce most men to skeletons by working out, running at least, daily.

An overnight flight delay, that was something Erik Anthony Audé could handle.

|

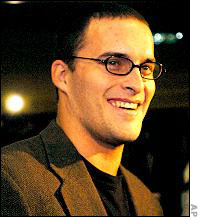

| Erik's return at the airport |

It was the day after Christmas when Erik finally arrived home. He sounded tired, and perhaps, physically a little weaker than the last time we spoke. But that false bravado that had occasionally crept into his voice when we chatted through the steel grate in Rawlapindi was gone, replaced with a kind of quiet strength.

He talked a bit about his plans - while in prison he had written a screenplay about his ordeal and with his mother's help, he now hopes to see it produced.

But most of all, he seems to want to express gratitude to all of the people who believed in him.

The words are simple, but they vibrate with the images of all he endured, and the deep respect for the faith his friends and family had in him.

"It's good to be home," he said. Then added simply, "thank you."